by Angelique Jackson

Black filmmakers are offering an unvarnished look at the legacy of the 1960s civil rights era, examining America’s tortured history of racism and drawing parallels to contemporary cries for social justice in some of the year’s most captivating films.

Regina King’s “One Night in Miami,” Shaka King’s “Judas and the Black Messiah” and Spike Lee’s “Da 5 Bloods” serve as a triptych of the Black experience, inviting viewers inside the great debates that accompanied an earlier generation’s fight for equality. Together, they chart the course of that turbulent decade.

Lee has spent his career spotlighting Black stories that have gone unshared or were framed inauthentically in the history books, most famously with 1992’s “Malcolm X,” which gave audiences a new view of the man behind the fiery speeches, but the director “practically killed myself to get made.”

“Black folks are part of American history, American her-story,” Lee says. “Right now, there are more films being made about our past than ever before.

“The studio heads are more apt to make these films than they were in the past. It’s not that Black filmmakers weren’t trying to do these films. It’s always come down to us telling our stories versus somebody else. I know Regina; Shaka was a student of mine. The more the merrier.”

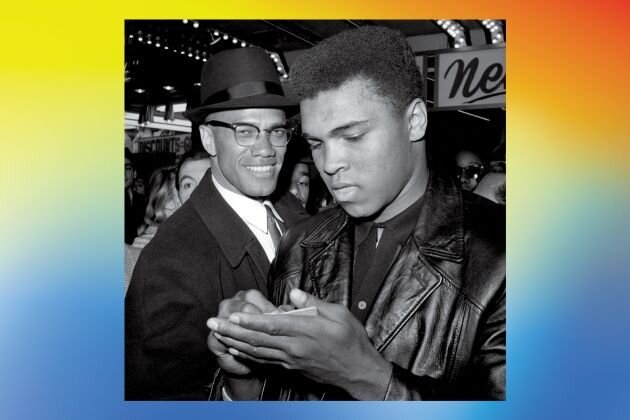

“One Night in Miami” is based on the real-life encounter between Malcolm X, Sam Cooke, Jim Brown and Muhammad Ali. It’s set on Feb. 25, 1964, the night the boxer (then Cassius Clay) won the heavyweight title for the first time. “Judas and the Black Messiah” takes place in the late 1960s and documents the final days in the life of Black Panthers leader Fred Hampton, while “Da 5 Bloods” travels between the Vietnam War era (with a scene in 1968 in which the titular Bloods learn of the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.) and the present, as the surviving quartet cope with the scars of war.

These filmmakers double as historians, contextualizing the past to determine how we got to where we are. King (credited for writing the “Judas” story with Will Berson and the Lucas Brothers), Lee (who partnered with Kevin Willmott for “Bloods”) and Kemp Powers (who adapted his “One Night in Miami” play for the screen) detail their process.

Why did you want to look back at the 1960s through the lens of today? What lessons can audiences take away?

Spike Lee: I was a kid growing up in that era; I remember it. In ’67, I was 10 years old. Thank God, I’m not old enough to be drafted, but the Afros, the music, Black Power, Dr. King getting assassinated, RFK assassinated, the Vietnam movement, the anti-war movement. I remember watching the Chicago Democratic convention on television in 1968 when Mayor Daley unleashed those cops cracking heads, and anti-war marches. That time was very rich.

Kemp Powers: We live in a country that it’s almost incredible how we’re able to contort ourselves to avoid discussing race in any way, shape or form, but every once in a while, it bubbles to the surface. And I think the 1960s were a crucible moment in the history of the country, as far as race relations. And I think we’re living through another crucible moment now, these past five or six years.

So much of the change is brought about by young people. That’s what really drew me to the night that I focused on for “One Night in Miami” — it wasn’t just that these were four famous men, but it was just reminding myself of how young they were. That Cassius Clay was 22, that Jim Brown was 28, that Sam Cooke was 31, that Malcolm X wasn’t even 40 yet.

And it was interesting for me watching “Judas and the Black Messiah.” My knowledge of the Black Panthers doesn’t go that far beyond Huey P. Newton. I knew who Fred Hampton was, I knew about his death, but at no point did I think all that happened to a man who was 21 years old.

That youth component inspired me, because I feel like young people need to be inspired to pick up the mantle and realize that they have this amount of power.

Shaka King: To piggyback off what you said about youth, Fred Hampton’s phone was tapped by the FBI at age 14; he was an NAACP youth leader at 16. Youth is the lifeblood of revolutions across the globe, because young people don’t have stuff to rope them in and fool them into thinking that everything is OK. Their life is in front of them, and they’re impatient in the best way.

During the rebellions of the summer, that was a very youth-led movement. I’m 41, and a lot of times, my generation and certainly the generations above us think of that younger generation as not really having any spine and backbone and having resilience. But I think nothing could be further from the truth.

What they’ve had to circumvent in their childhood and adolescence, and the ways in which they’ve responded, has been really impressive. I’ve heard the revolutionaries in their 60s [now], who were the young people in the Black Panthers, talk about how this feels different and, in some ways, even bigger than when they were the folks on the front line.

What was your process in preparing to tell these stories?

Lee: Research, research, research, research and more research — documentaries, films, books, everything I could get.

Powers: I would argue that when it comes to both Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali, everyone’s an expert and knows more about them than you do, and that’s OK. I never profess to know everything. I’m just a guy who’s read a lot of stuff and done a lot of reporting.

But even when it’s a person that you know so well, it’s always interesting to try to look at it from a slightly different angle; it can change the meaning of that moment. That’s why I really wanted to make this a piece of historical fiction, because there’s a certain burden to try to fairly characterize each of these men. Even though the words that they’re speaking are words that you’re making up, you do have a burden.

However, this is not supposed to be a biopic. This is just to give you an understanding of what these men represent, rather than what they did, when and how. This isn’t supposed to be your historical document. If anything, quite the opposite; it’s supposed to make you go out [and read]. The FBI files on Malcolm X have been available for years; you can track everything the man did the last year of his life.

King: The only difference for me is that not as much is known about Fred Hampton and the Illinois chapter of the Black Panther Party as the individuals in “One Night in Miami.”

But nevertheless, in the writing process, in our first draft, my co-writer Will Berson and I had the address of the apartment and the Better Boys Club in the slug line. When you’re trying to regurgitate everything you’ve learned — which, for us at least, a lot of it was ego; we wanted [the audience] to know we did our jobs — but when you do that, you end up with a script that’s like 205 pages and not at all dramatic.

It took five or six drafts before we got out of our own way and allowed ourselves the freedom to treat this more like historical fiction and make a movie about ideas. Let’s make this movie about these two people, and let these two people represent and serve an exploration of these opposite poles of humanity — socialism or capitalism — and allow the viewer to watch and see if you connect with both of them in any way, or see where you fall in between those two poles, even on a subconscious level. We just thought that was more interesting and more useful.

If you watch these movies, leave and go to Wikipedia or Google some books, maybe buy one or two, that’s the best that we can hope for in terms of aiding in these individuals’ legacies. Young people probably don’t know about these folks, so there’s an opportunity for them to learn their history.

Let’s talk about the music. Spike, Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On” album was an important thread. How did it help you shape the narrative?

Lee: Like a surgeon, I did it very skillfully [laughs]. He was a prophet. “What’s Going On,” one of the greatest albums ever made, came out in 1971. I know the album back and forth, and I knew where to put the songs.

When Kevin and I decided to do this movie, I automatically thought the song “What’s Going On” could be the spine of the film. “Inner City Blues” was the first song that came to me because I knew I wanted the film’s opening sequence to be archival footage. And then we had the Bloods singing “What’s Happening Brother” in the film.

Kemp, Sam Cooke is a player in your story, how did his music influence the film?

Powers:Your gut reaction is to get all the biggest Sam Cooke songs out there, but I felt like that wasn’t what served the story. What was important to me was getting elements of Sam’s process and influences into the song selection.

From the very beginning, with the play, I knew that “A Change is Gonna Come” was the crux of the story. But, in terms of the other music, Sam was very much an observational songwriter. “A Change is Gonna Come” is the epitome of that, but that started way back during his gospel roots, singing with the Soul Stirrers, which is why I structured it around “Put Me Down Easy,” which is actually a song that he just wrote for his brother L.C.

It’s not a biopic, so it wasn’t about, “When are we going to have the next Sam Cooke musical number?” In fact, the biggest musical number in the stage play, is not in the film — the recreation of his performance at the Harlem Square Club in 1963, that’s something that, in the play, is a show-stopping moment. But it didn’t serve the story.

Telling people about the screenplay, I always would warn them, “You’re going to get a movie with a singer, with not much singing; a boxer, but not much boxing; a football player with no football scenes; and Malcolm X, not giving any speeches.” That wasn’t really what the story was about. You should leave this film and want to hear a lot more Sam Cooke.

How have the streamers changed the road for films like these to get made?

Lee: The streamers are more doors to knock on. You only need one, and Netflix was that one door, and I thank them. The more places that make films, it just makes sense that more, different films will be made.

King: Obviously, people have been asking me about this because our movie is coming out in theaters and on HBO Max the same day, and this is new. But one thing that I immediately found exciting was that we were not only going to get it to more people, but because of the pandemic you’re literally talking about a captive audience — people who can’t go outside.

You have an opportunity to put a movie in front of someone who probably wouldn’t have watched it, or might have been turned off to the

politics, or made the easier choice to go see like a tentpole because you know we can bring the kids and everybody. But now it’s like, “OK, well, why not watch ‘Judas and the Black Messiah’? The trailer was cool.” And maybe there’s some information and medicine that’s contained there, and it’s beneficial.

Powers: When you write these screenplays, you have no idea how it’s going to ultimately be realized. In a normal year, let’s say all these films had been released in theaters; people would have been forced to make a choice. This year is interesting because I would argue that anyone who’s seen “Da 5 Bloods” probably has seen “One Night in Miami” and will probably see “Judas and the Black Messiah,” and I don’t think that would have necessarily been the case with all three of them released in theaters. Instead, it’s like, wow, people are getting to take in all of these films, and that’s just three.

These past 10-15 years, it’s just been a series of pendulum swings in terms of people’s boldness; I was talking to a friend of mine, just marveling at the bumper crop of films that came out this year. And I wondered, “Is this because of Trump?” Did people finally say, “Well, we’ve got nothing else to lose? A lot of the work that I’ve seen is very bold, like Shaka’s film, down to the title. I think that’s a very bold title to lean into and it’s commendable. There’s just an in-your-face boldness to so much of the work that I’m seeing; I just hope the pendulum doesn’t suddenly swing another way and people revert back to safety mode, because we have a new administration.

The one thing that I think everyone should realize is there is no back to normal anymore. We’re going to be in like a brave new world. I hope that this encourages more people to be bold in their filmmaking.I love “Da 5 Bloods,” but 10-15 years ago, a Spike Lee movie would have been the event that we all had to wait for, and that would be it — that’s your honest Black movie for the next two years. We don’t have anything else. And now it’s like sweet, the tree is bearing a lot of fruit.

King: I think it actually is because of Trump. My friend, filmmaker Mtume Gant, called the wave of Black cinema and TV around “Selma,” “Moonlight, “Atlanta,” he called it the Black Excellence Industrial Complex. That’s brilliant because it sums it all up.

Companies finally realized that movies, by us, starring us, could make money, and started investing in them, so they could make some money. I think, President Obama really ushered in that in a lot of ways, on a cultural level, just being the most famous person on the planet, being Black, and being president. And then I think when Trump came in, a lot of Hollywood is an incredibly white and liberal town and the same way that Trump ushered in a culture that was racist, hateful, sexist, misogynistic, and it was mainstream, I think there was a reaction to that.

That didn’t change me, I’d been wanting to make movies like this my entire career, I just had a little bit more access to it now because they were willing to counter that rhetoric with equally, brash loud [filmmaking]. Ultimately, it depends upon the success of our movies financially. You can hope for a Black Radical Industrial Complex, but it’s only if our movies are successful.

Powers: That’s the thing – people have been asking me, “Where have you come from?” I’ve always been here telling stories. The only thing is now all of a sudden people want to do it. That’s not credit to me, it’s credit to the political environment we’re in, because what stopped “One Night in Miami” play from going as far as it did, is because of the perception that it would alienate white audiences.

It’s so nice that being unapologetically Black is in now, because it wasn’t four years ago. And I know it wasn’t, because my voice wasn’t as well received. You’re talking to a guy who just did a Disney movie. What they read of mine that made them interested in me on “Soul” was “One Night in Miami;” that was my sample. So, when I came on board, I realized, “Oh, they know what they’re getting.” Usually that’s the type of sample that would stop you from getting a job, in years past. It’s interesting that people are interested in your voice because I’ve been telling these stories for years, it’s just now that people seem to be receptive to them.