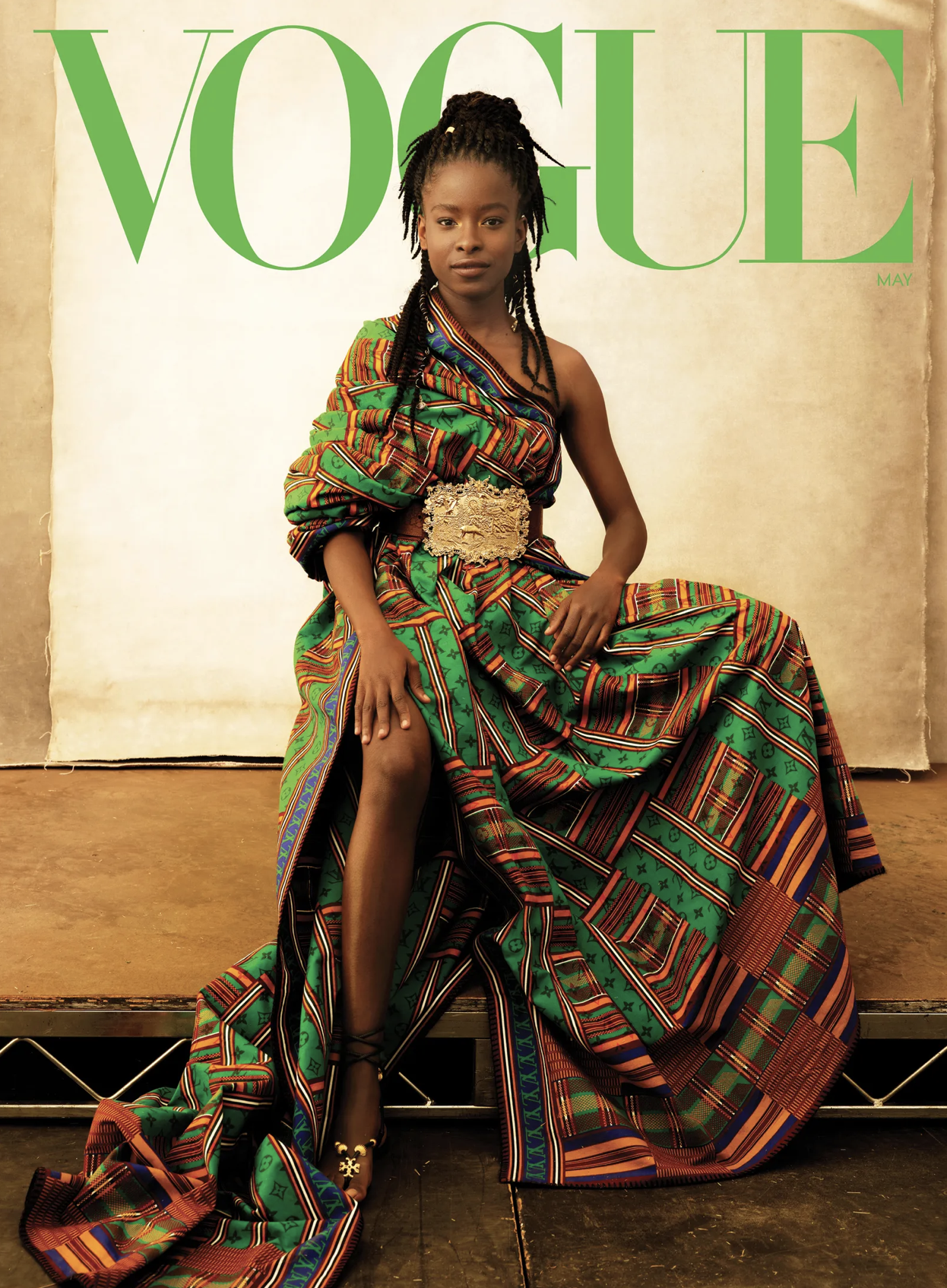

Gorman described all this with some dissociative distance, as if, that day, she’d been a member of the at-home throng and not on the platform at the West Front. “Not that no one else could have done it,” she told me. “But if they had taken another young poet and just been like, ‘A five-minute poem, please, and by the way the Capitol was just almost burned down. See you later.…’ ” She drifted off, her booming voice diminished to a whisper, and then returned. “That would have been traumatizing.”

She asked her advisers. Oprah— who’s been a fame doula to Gorman since they first met on John Krasinski’s YouTube show Some Good News in May of last year—told her to look to the example of Angelou. (“Every time I text Oprah, I have a mini–heart attack,” Gorman jokes, holding her iPhone at arm’s length.) Wicks, who met with me over Zoom after a long day of teaching, encouraged her daughter to keep the appointment because she sees Gorman as a writer who is duty bound to serve democracy. “I did have Amanda practice,” Wicks said and lifted her eyes to the ceiling for a few seconds, “how, in a second’s notice, I could become a body shield.” She described crouching over her child in the hotel room the night before.

Just five days before the inauguration, Gorman texted someone at Prada, back then the one fashion house with which she had a connection, and they sent over the outfit and the headband. The red accessory had looked silly, placed at the fore of her head, so her mother suggested Gorman wear it like “a tiara, a crown.” Gorman did her makeup herself. It snowed lightly the morning of the inauguration. On the stage, Wicks warmed her daughter with blankets. She was shivering. And then, all of a sudden, she was not. “Her nerves don’t show up” in the moments leading to showtime, Kisner, the stage director, told me. “They’ve been processed and dealt with before she walks in the door.”

With all the commotion following the performance, it took Gorman an hour to get back into the hotel. On our patch of green space she pulled a journal from her tote. Clearing her throat, she read from the entry she wrote that night, redacting a few lines as she went: “I’ve learned that it’s okay to be afraid. And what’s more, it’s okay to seek greatness. That does not make me a black hole seeking attention. It makes me a supernova.”

In one’s memory of the reading, it is the delicate pair of hands, whirling like those of a conductor, that stand out. Gorman developed the movements as a guardrail of sorts, to remind her to slowly pronounce any consonants she has difficulty with. They flutter downward on “descended from slaves,” and tickle up, on “raised by a single mother.” “Skinny Black girl,” in the single autobiographical line, is the thrillingly out-of-place phrase, for me. All of a sudden, this galvanizing appeal, tailored to move the populace, constricts to the perspective of the individual. The “we” of the poem goes dormant, and we can see into the personal life of the speaker. “They are like essays,” she told me of the work she writes for big audiences. “They have a thesis, an introduction, and a conclusion.”

The argument put forth was this: “But while democracy can be periodically delayed, / it can never be permanently defeated.” To many, depleted of optimism, that pair of lines was a purging of Trumpism. Her publisher, Viking, rushed to package the text of “The Hill We Climb” as a paperback keepsake. On the page, the verse reads differently, less urgently. The words require her crisp and enunciating powers to feel vivid. Wicks knows that Gorman’s chemical presence is the key. “You could have two poets,” she said, “and one can actually have more talent. But Amanda’s the one who is going to work the room.”

“It’s like they made her poetry,” said the poet Danez Smith of the ravenous media response to Gorman. Smith has seen Gorman perform and admired the “political heart and mind and attention to history and community” evident in all her work. The first true piece of poetry criticism Gorman ever published, for the Los Angeles Review of Books, was an exacting close reading of Smith’s “Homie,” in which Gorman identified the “fetishization of suffering and violence” rampant in the liberal imagination. Gorman has now been recruited into that cultural imagination. Does the nature of her introduction to a larger readership cast her as a satellite of the Biden administration? Does the poet who speaks from the corridors of power concede something? There is the classical idea of the poet as the gadfly, who lives outside society. Because Gorman is a public figure, all of these projections and strong feelings she engenders are a part of her work. “I wonder what the journey is for a political poet,” Smith said. “I hope we don’t limit her to that poem. I hope we don’t think that she’s always got to talk to everybody.”

Gorman has said that she wants to be president. She notes that she has the unofficial endorsements of Hillary Clinton and Michelle Obama

Following the inauguration, Gorman’s phone, blowing up with notifications, was too hot to touch. Her follower counts on social media ballooned by hundreds of thousands. In one of our conversations, she cautiously brought up a Washington Post article that had been written on her phenomenon, aware that she might sound self-involved. “Skip over the parts about me,” she said. “The great part is where they’re talking about how, historically, poets have been pop stars.” She listed Longfellow and Wheatley. To Gorman, the concentration of attention, and resources, on the form she loves is a net gain, although she is aware of the inevitable drawbacks of a consumerist and capitalistic dynamic.

You know how it is. A young woman is clear about what she cares about, makes compelling work, and the power brokers don’t know how to act. They venerate her voice to oblivion. The celebrity of Gorman and other comparable young figures, who become vaunted for their erudition and moral clarity and their bright elucidation of global pain, is a new, and complicated, kind of fame. The writer and performer Tavi Gevinson, who knows something about popularity and fetish, met Gorman in Milan at a weekend-long Prada event two years ago. She told me she’d felt relieved to have someone with whom she could talk books. In that overwhelming press cycle after the inauguration, Gorman became a magnet for the “escapist fantasy,” Gevinson said, of the fragile-but-intimidating young woman who saves the world. Gorman is becoming increasingly careful of situations that would make her seem like a token. “I don’t want it to be something that becomes a cage,” she said, “where to be a successful Black girl, you have to be Amanda Gorman and go to Harvard. I want someone to eventually disrupt the model I have established.”

Gorman wanted to show me her quarantine world. She joked that its circumference couldn’t be more than a mile-and-a-half long. We were to walk a winding trail that would take us through some manicured brush and wetlands, only to deliver us to one of the best views of L.A. anyone could find. Gorman was running a little late. She texted me her apologies along with a funny duck-face selfie; her face was covered in the white film of crappy drugstore sunscreen. The day before, she’d gotten a minor case of the dreaded face-mask sunburn, which got us talking about how annoying it is to find protection tailored to our skin.

When she met me near the trail, I told her that the selfie made me think of that episode of Donald Glover’s surrealish FX comedy Atlanta, the one where Antoine Smalls deadpans, “I’m a 35-year-old white man.” Giggling as I explained the episode’s plot, on whiteness and Blackness as inherent farce, she revealed to me that she hadn’t seen Glover’s series. Or much television, actually. It “was The Munsters and The Honeymooners,” she said, when she was growing up in West L.A. If she wanted to watch something from the 21st century—Disney’s animated action comedy Kim Possible, say—she had to make an argument to her mom that the show had good politics.

The third time the television sizzled out in Gorman’s childhood home, Wicks decided not to fix it. The girls were livelier, more creative, when they found ways to entertain themselves. There were plays, homemade films, and botched science experiments. All the while Wicks was pursuing a doctorate in education at Loyola Marymount University. The family sometimes struggled financially. The twins were born prematurely; when she was a baby, Gorman’s head was too heavy for her body, and so she devised a way to push herself along, flat on her back, from the torso, like a belly-up flounder, which she demonstrated to me the day we hung out on the green. The twins both had difficulties with speech. Because Amanda also had an auditory-processing disorder, she could not pronounce the letter r. The family tried therapy, tongue depressors; Gorman exiled words that used the consonant. But there was always a surname, always the word poetry. Education, for Wicks, was paramount. The girls attended New Roads, a progressive learning institution in Southern California.

Growing up, Gabrielle, a talented filmmaker in her own right, was physically stronger than her sister. Amanda was the writer, compulsively, from about age five, stealing time from her sleep to draft short fiction, inspired by Anne of Green Gables. “My mom had to give me a quarter so I’d sleep past 5 a.m.,” she told me on our hike. She applied for L.A. Youth Poet Laureate when she was 16. “I was like, ‘Well, I guess, I’m a poet.’ ” Her early performances were for live shows like WriteGirl, The Moth, and Urban Word and conferences like TED Talk and Vital Voices—the leadership organization for young women that once gave her a fellowship and counts Clinton as a founder. “Roar,” at The Moth, is a charming retelling of the time she auditioned for Broadway’s The Lion King. The poem is riddled with r words, and Gorman takes joy in the effort of pronunciation. Her delivery is rather like a comedian’s; to better illustrate a point about hyenas, she abruptly flips and does a walking handstand.

Gorman spent her college years balancing classes in English, sociology, and the writing workshop she founded, Lit Lounge, with speaking gigs and poetry performances that took her everywhere from the White House to Slovenia. For Gorman, who is grounded by the principles of Black feminism, writing and activism were always linked. At 16, she founded One Pen One Page, a youth literacy program. Now, after years of commissions and prestigious fellowships, she can afford to rent her apartment situated its lush, middle-class environs. “I’m trying not to judge myself,” she said, chewing on the gummi bears she’d brought. “When you’re someone who’s lived a life where certain resources were scarce, you always feel like abundance is forbidden fruit.”