‘What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July?’ Douglass demanded in 1852

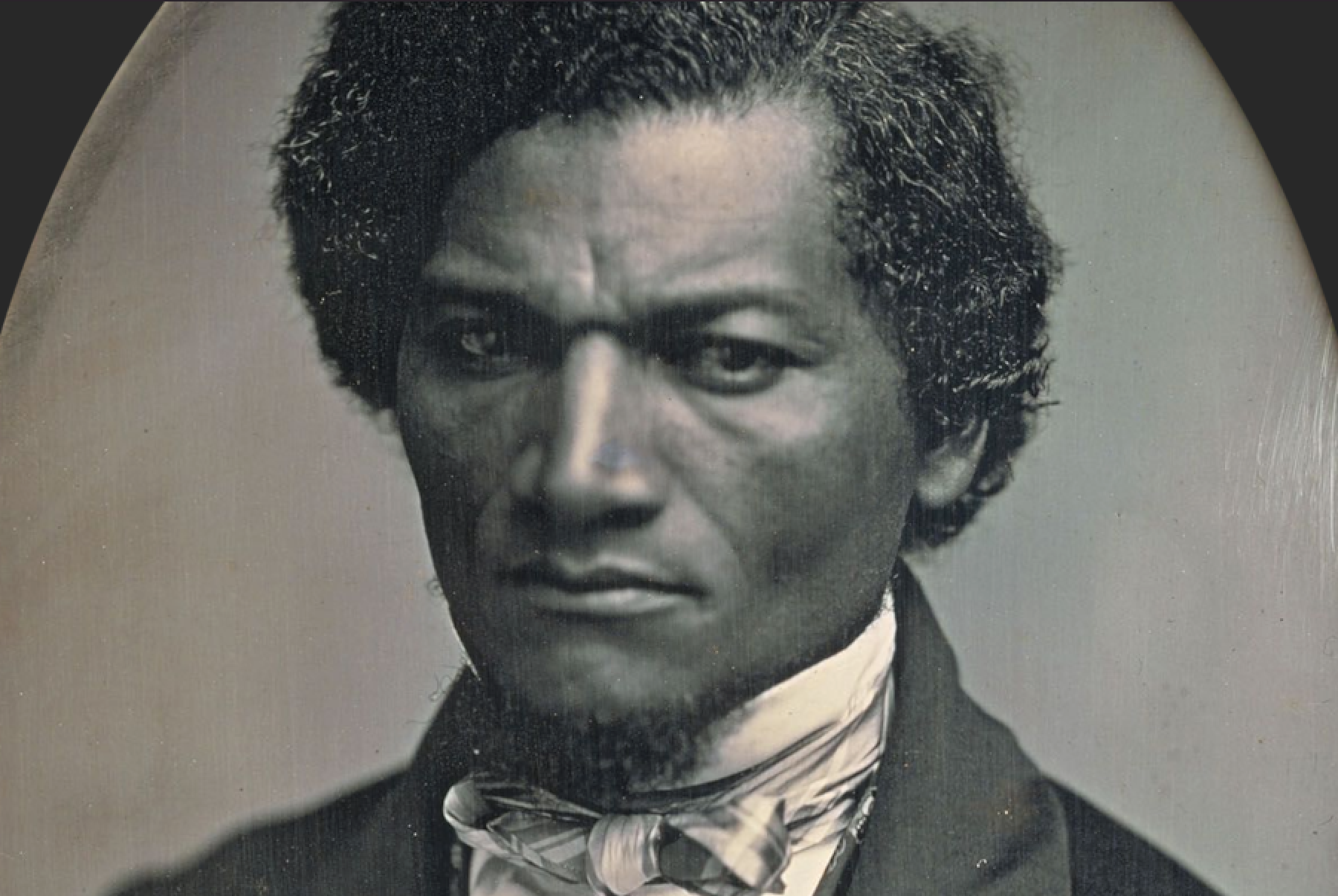

Frederick Douglass circa 1852, when he was in his mid-30s. (Samuel J. Miller/Art Institute of Chicago)

“The papers and placards say that I am to deliver a 4th [of] July oration.”

So began Frederick Douglass on the platform of Corinthian Hall in Rochester, N.Y. It was a Monday, the day after the Fourth of July in 1852, and he was speaking to a packed room of 500 to 600 people hosted by the Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society. Douglass was about 35 years old (he never knew his actual birth date) and had escaped enslavement in Maryland 14 years earlier.

Although by this time he was world-renowned for his speeches, he began modestly, reminding the crowd that he had begun his life enslaved and had no formal education.

“With little experience and with less learning, I have been able to throw my thoughts hastily and imperfectly together,” he began, “and trusting to your patient and generous indulgence, I will proceed to lay them before you.”

Over the next hour and a half, Douglass made what is now thought to be among the finest speeches ever delivered: “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” He quoted Shakespeare, Longfellow, Jefferson and the Old Testament. He certainly bellowed in moments, exclaiming and anguishing in others. He painted vivid pictures of exalted patriots and the wretched of the earth.

First, he posited that while 76 was old for a man, it was young for a nation. America was but an adolescent, he said, and that was a good thing. That meant there was hope of its maturing vs. being forever stuck in its ways.

He wove through the familiar tale of taxation without representation, tea parties and declarations of independence. “Oppression makes a wise man mad,” he said. “Your fathers were wise men, and if they did not go mad, they became restive under this treatment.”

Perhaps at this point it was imperceptible to his audience that Douglass repeatedly said “yours” and not “ours.” Did they notice the hint of what was to come?

Frederick Douglass delivered a Lincoln reality check at Emancipation Memorial unveiling

But his business was with the present, not the past, he said, and here his critique began to build.

“Fellow-citizens, pardon me, allow me to ask, why am I called upon to speak here today? What have I, or those I represent, to do with your national independence? Are the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice, embodied in that Declaration of Independence, extended to us? and am I, therefore, called upon to bring our humble offering to the national altar, and to confess the benefits and express devout gratitude for the blessings resulting from your independence to us?”

...

“The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought life and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth [of] July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn. To drag a man in fetters into the grand illuminated temple of liberty, and call upon him to join you in joyous anthems, were inhuman mockery and sacrilegious irony. Do you mean, citizens, to mock me, by asking me to speak to-day?”

...

“At a time like this, scorching irony, not convincing argument, is needed. O! had I the ability, and could I reach the nation’s ear, I would, today, pour out a fiery stream of biting ridicule, blasting reproach, withering sarcasm, and stern rebuke. For it is not light that is needed, but fire; it is not the gentle shower, but thunder. We need the storm, the whirlwind, and the earthquake. The feeling of the nation must be quickened; the conscience of the nation must be roused; the propriety of the nation must be startled; the hypocrisy of the nation must be exposed; and its crimes against God and man must be proclaimed and denounced.

“What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer: a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciations of tyrants, brass fronted impudence; your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade, and solemnity, are, to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy — a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages. There is not a nation on the earth guilty of practices, more shocking and bloody, than are the people of these United States, at this very hour.”

...

“Behold the practical operation of this internal slave-trade, the American slave-trade, sustained by American politics and America religion. Here you will see men and women reared like swine for the market.

“You know what is a swine-drover? I will show you a man-drover. They inhabit all our Southern States. They perambulate the country, and crowd the highways of the nation, with droves of human stock. You will see one of these human flesh-jobbers, armed with pistol, whip and bowie knife, driving a company of a hundred men, women, and children, from the Potomac to the slave market at New Orleans. These wretched people are to be sold singly, or in lots, to suit purchasers. They are food for the cotton-field, and the deadly sugar-mill.

“Mark the sad procession, as it moves wearily along, and the inhuman wretch who drives them. Hear his savage yells and his blood-chilling oaths, as he hurries on his affrighted captives! There, see the old man, with locks thinned and gray. Cast one glance, if you please, upon that young mother, whose shoulders are bare to the scorching sun, her briny tears falling on the brow of the babe in her arms. See, too, that girl of thirteen, weeping, yes! weeping, as she thinks of the mother from whom she has been torn!

“The drove moves tardily. Heat and sorrow have nearly consumed their strength; suddenly you hear a quick snap, like the discharge of a rifle; the fetters clank, and the chain rattles simultaneously; your ears are saluted with a scream, that seems to have torn its way to the center of your soul! The crack you heard, was the sound of the slave-whip; the scream you heard, was from the woman you saw with the babe. Her speed had faltered under the weight of her child and her chains! that gash on her shoulder tells her to move on.

“Follow the drove to New Orleans. Attend the auction; see men examined like horses; see the forms of women rudely and brutally exposed to the shocking gaze of American slave-buyers. See this drove sold and separated forever; and never forget the deep, sad sobs that arose from that scattered multitude. Tell me citizens, WHERE, under the sun, you can witness a spectacle more fiendish and shocking. Yet this is but a glance at the American slave-trade, as it exists, at this moment, in the ruling part of the United States.”

He also indicted the American church, “with fractional exceptions,” for its “indifference” to the suffering of the enslaved, its willingness to obey laws so clearly immoral. It was a theme echoed a century later by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in his “Letter From Birmingham Jail.”

The church, Douglass charged, “esteems sacrifice above mercy; psalm-singing above right doing; solemn meetings above practical righteousness. A worship that can be conducted by persons who refuse to give shelter to the houseless, to give bread to the hungry, clothing to the naked, and who enjoin obedience to a law forbidding these acts of mercy, is a curse, not a blessing to mankind.”

The Statue of Liberty was created to celebrate freed slaves, not immigrants, its new museum recounts

He turns to the Constitution, and here he defends it and raises it up as a pathway to liberation for the enslaved.

“In that instrument I hold there is neither warrant, license, nor sanction of the hateful thing [slavery]; but, interpreted as it ought to be interpreted, the Constitution is a GLORIOUS LIBERTY DOCUMENT. Read its preamble, consider its purposes. Is slavery among them? ... [L]et me ask, if it be not somewhat singular that, if the Constitution were intended to be, by its framers and adopters, a slave-holding instrument, why neither slavery, slaveholding, nor slave can anywhere be found in it. What would be thought of an instrument, drawn up, legally drawn up, for the purpose of entitling the city of Rochester to a track of land, in which no mention of land was made?”

That is why, he said, despite the “dark picture” he painted, “I do not despair of this country.”

“There are forces in operation, which must inevitably work the downfall of slavery. ‘The arm of the Lord is not shortened,’ and the doom of slavery is certain,” he says. “I, therefore, leave off where I began, with hope.”

When he finished speaking and took his seat, “there was a universal burst of applause,” according to one newspaper account. Within a few minutes he had promised to publish his words as a pamphlet.

Douglass was right. The forces that would end slavery in little more than a decade were in operation, and he was one of those forces.

But he couldn’t see what would follow: sharecropping and Jim Crow, redlining and Bull Connor, incarceration rates and George Floyd. Would Douglass still figure us an adolescent nation, with the youthful hope of transformation — or something else?