It was 88 years ago, in July 1932, that a color photo first appeared on the cover of Vogue. It featured a woman in a bathing suit holding a ball, and in its graphic simplicity it had something of an illustrative quality. This was a watershed moment for the still young medium of fashion photography, but also for fashion illustration, which for so long had been the lingua franca of the mode. To be clear: Vogue had used photographs before this time, and would continue to use illustrations after it, but the power dynamic had irrevocably shifted. Technology, it seemed, had triumphed.

Illustration never went away, of course, but, as with couture, its purview narrowed and it became more specialized. Both metiers elevate handwork and the individuality that it brings. The feeling of closeness evoked by handwork, which illustration delivers, has become even more desired as we have been isolated from each other amid the pandemic.

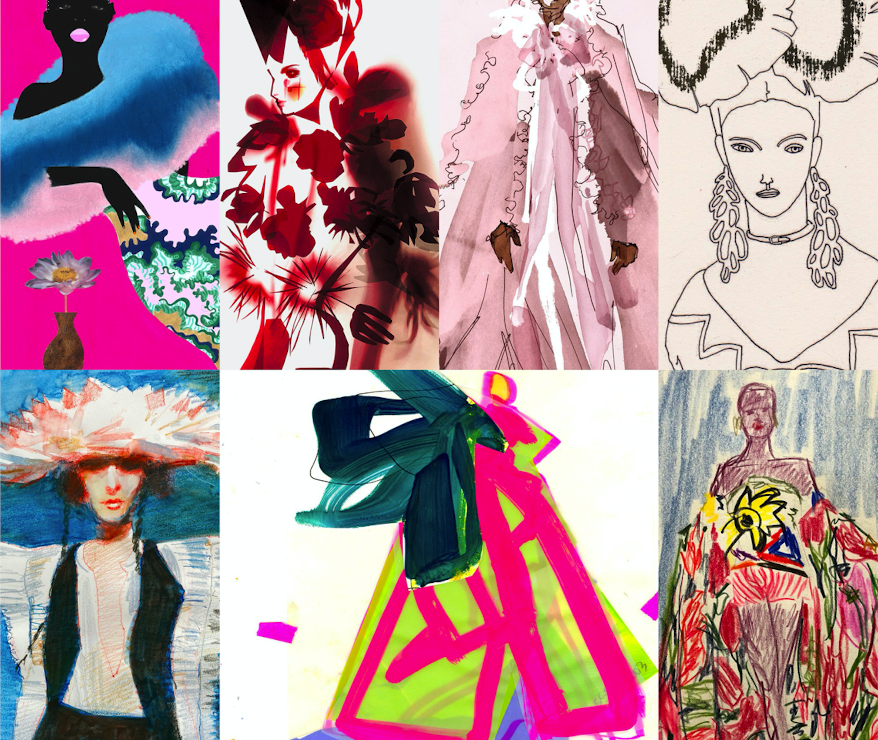

Here, we honor the art of illustration with drawings of looks handpicked from the Vogue Runway archive by seven artists. This is how they see the couture.

Grace Lynne Haynes, @bygracelynne

An inaugural member of Kehinde Wiley’s Black Rock Senegal residency, Grace Lynne Haynes, a New Jersey–based Californian, studied illustration before turning her attention to painting. Taking as her subject “complex topics and stereotypes surrounding Black women and femininity,” Haynes’s paintings are distinguished by the contrasting of bright colors with powerfully flat and graphic silhouettes of black paint “shaped,” she says, “to represent Black female bodies. In my work, she continues, “black appears aspirational, dignified, and sublime.”

“For this project, I chose Valentino’s fall 2019 couture show. This show stood out to me because it set a new template for collections with a conscience. Valentino’s Pierpaolo Piccioli chose to feature several Black models, challenging the token Black model stereotype. His message of inclusivity is resonating in a world in which our leaders seem keen to promote isolationism, otherism, and fear. Piccioli said, ‘The only way to make couture alive today is to embrace different women’s identities and cultures.’ I firmly stand with this sentiment. In our current political climate I find it is important to showcase the Black female figure not only as strong, but elevated and empowered, yet divine.”

Jacky Blue, @jackyblue__

There seems to be lightning in Jacky Marshall’s line; there’s a positive energy that pulses through her color-drenched drawings and collages. Trained as a designer, this Brit knows fashion inside out, and loves it, as her drawings clearly show.

“ I love that Margiela collection, every time I look at it I see something different. The thing about that collection is, for me, having trained as a designer and not as an artist, it’s the kind of thing I would have loved to have designed myself. I love the deconstruction side of things, I love the silhouettes; the colors are amazing.

I started playing around with anything I had around me and collaging. I literally just did it; I just went with the flow. I can have an idea, but I never know until I start. I don’t approach everything the same way, my lines aren’t the same for every designer I draw. [For this drawing] I played with layers. I hand-print my own paper to use, and I happened to have a color that was similar, but it’s also layered with colors behind it. When I bought the paper, they numbered it, and I liked it, so I kept it.”

James Thomas, @jamesthomas

James Thomas has a gift for imbuing abstracted silhouettes and figure studies with an airy poetry. A creative director in fashion for many years, this London-born, New York–based artist creates large-scale paper-cut collages in which blocks of color are syncopated with meditative white space.

“I was inspired to illustrate one of my favorite haute couture looks from Givenchy fall 1996 because it expresses a clear narrative, a larger-than-life concept, and a generosity of spirit: the hallmarks of haute couture.

I set up this illustration by building a life-size canvas on a light box, onto which I collaged acetate paper on three surfaces of glass to create depth and shadow.”

Sara Singh, @sarasinghillustration

There’s a liquid quality to Sara Singh’s work that she maintains as she patiently layers her while ink and a brushwork in layers on the computer. This wet line is more expressive than exact, and Singh, a transplanted Swede, uses it to make dramatic statements that are not mired in detail, but get straight to the heart of her subjects.

“I chose this dress because it looked fluffy and protective, and it was worn by Alek Wek. She has her own look, a natural look—she doesn’t have straightened hair—she has her own beauty. And she got to wear the wedding dress and she was Black, which was unusual at that time. I just thought it was such a strong image.

The drawing is pen and ink and ink washes, and then I scan all the different drawings and layer them in Photoshop.”

Frida Wannerberger, @fridawannerberger

At first glance there might seem to be a floaty, paper doll quality to Frida Wannerberger’s drawings of women; but look closer and read the titles of the works, and it’s clear that these are women, not girls, not playthings, and that they use fashion to navigate their complex worlds. And like Wannerberger, a London-based Swede, her women tend to have penchants for puffed sleeves.

“I’m fascinated by the ways in which dress has, and continues to be, linked to history and how we progress as societies [in terms of] identity, power, and seduction. [When I was] growing up in the mid 2000s, the couture shows were the pinnacle of staged narratives—I was fascinated by how many small details (of a look) worked together to make up a character (look) that plays a part of a larger narrative (show, ad campaigns, editorials).

John Galliano and his Saint Martins trajectory was the reason I wanted to study at CSM, so it’s mainly due to this collection—and thorough studying of the Runway Supplement bibles 2003–2006—that I am in London! I chose to be quite selective with the details here, bringing the headpiece, the sense of adornment around the face through the jewelry and the necklace, into focus. The elaborate full skirt is bleeding off the page.

I worked with a fine liner on 300 GSM watercolor paper. It’s an odd size that originates from leftover paper scraps from a commissioned project. I got used to the size and enjoy working with the crop / placement of the body on the paper. I always start with the eyes, then the rest of the face, and let that guide me with the rest of the figure. I enjoy just working with the lines; it’s very meditative for me. I sometimes sketch out indication lines for various options of angles of the body, but I do enjoy being quite assertive with my marker and seeing where it takes me.”

Chris Gambrell, @gambrell_

In his quick sketches, Chris Gambrell is able to convey character through the smallest gestures. His finished works are moody studies of color and texture. Having gotten “up to his eyes” in the Vogue Runway archives, from his hometown of Bristol, England, he whittled 50 selects down to just one.

“I drew look 12 of Jean Paul Gaultier’s spring 2010 couture collection because its drama and beauty was crying out to be rendered in inky textures. This look stood out for me because of its balance and imbalance; the weight of the broad shoulder section with the tapered fringe-like epaulettes meeting the extensions of the hat and everything tipping and swinging to one side, you can feel the movement. Like a cloud across a lilting horizon or Icarus meeting the elements, the drama drew me in.

As with everything I draw, the subject matter chooses itself, the dark textural background rendered in inky aquarelle throws the protected white areas forward with the marks of wax crayons an ode to the handmade nature of couture.”

Mary B., @mary_b_illustrations

Mary B., who is based in Amsterdam, uses colored pencils and oil pastel for her portraits and fashion drawings. There’s an engaging awkwardness to some of her work that, to this viewer, calls to the mind the unforgettable walk-stomp Leon Dame revealed on the runway at Margiela and was so riveting. Perfection can be off-putting, imperfection is invitingly human.

“What I love about couture is the craftsmanship and the dedication to the materials and fabrics. I wanted to grab that feeling and to catch the textures and prints in my drawings. For me it’s important that a drawing ‘lives’ and breathes. Drawing this haute couture dress from Lacroix was fun to do; it really obsessed me in a positive way! I used color pencils, and I chose this [ensemble] from spring 1988 because it’s still a very powerful look after so many years. It’s both chic and tough/cool with strong colors and a beautiful design.”

Subscribe to Vogue for the Latest in Fashion, Beauty and Culture